It all went quiet, the ‘Toril’ (Gates of Death) were flung open and 550-kilograms of prime Ecuadorian fighting bull charged across the freshly raked sand and into the centre of the arena. Separated from the herd and in a circular ring with no place to hide his hackles were up and everything in the ring was a potential threat. Selectively bred from Iberian cattle to possess an overwhelming urge to charge any aggravating shapes that appeared before him, everything had led to this occasion, his sole reason for being born at all, his fifteen minutes in the limelight, his time to die.A pair of ‘Toreros’ alternately lured the bull around the ring towards them with large sweeping movements of their capes. The bull, a powerhouse of energy and fight, chased everything down for a few minutes until he began to show his first signs of tiring. The Toreros then retreated behind their shuttered escape slots and the Toril opened again. This time a man carrying a long lance and mounted on a heavily ‘armoured’ horse trotted into the arena: the Picador. The bull, sensing another adversary, made a run at horse and rider, slowly slamming into the horse’s padded side. The horse leant into the bull’s advance whilst the Picador thrust his lance into the massive left shoulder muscle of the bull, the point only penetrating about 4-inches before being stopped by a wide collar on the shaft. The Toreros then distracted the bull away from the Picador whilst he made his exit from the arena. Now the ‘Bandilleros’ came into play: each holding a pair of short tasseled spears with barbed points they drew the bull towards them and as he charged they attempted to stick the ‘bandilleras’ into the shoulders. After a few minutes of this the bull had four bandilleras hanging off his back and a steady stream of blood running down each side.

It was time for the third and final act as the Matador entered the arena with his red ‘muleta’ (cape) and sword. With arched back and sneering facial gestures the Matador manoeuvred his cape in such a way that the bull charged dangerously close to him but never too close. The bull was now visibly tired but still pawed the sand in anger and charged at every movement of the cape. At last, sensing the time was right the Matador slowly approached the bull with raised sword and going in over the horns thrust it deep between the shoulder blades. The bull fell to his knees and keeled sideways onto the sand. With that final sword thrust I felt a sensation of mild nausea in the pit of my stomach, numbness and relief that it was now over for the bull. I shared none of the crowd’s euphoria and applause: what was this delight in witnessing a death?

Two more bulls came and went and in an awful realisation we noted that we were becoming habituated to this ritual slaughter. The fourth bull however did not succumb so easily. The Matador in making his final blow must have missed and gone into the bull’s lungs. The animal fell to its knees but then got back to his feet and continued to stagger around the edge of the arena, blood running out of his nose and mouth, disorientated, but still not giving up. At that moment we just wanted the bull to die and put an an end to this awful spectacle. Falling to his knees for the last time, a bandillero came in and severed the spinal cord just behind the horns, it was over.

In the days after the Corrida I was full of sound and fury. I was all for putting bullfighting in the same category as bear-baiting, dog-fighting, hare-coursing and cock-fighting. It was not a fight, it was not sporting and it most certainly was not fair. Spoken like a true Englishman! But it had been our first bullfight – or Corrida de Toros as they are properly known in the Spanish speaking world – and as casual attendees with limited prior knowledge it was always going to be a challenging experience. However, we are both familiar with life and death having spent considerable time in the country amongst animals: we are not squeamish; have killed for the pot; and are reasonably regular meat eaters. Thus we have already made that most supreme of moral decisions, something must die for our culinary pleasure.

At this point it is worth noting that since the advent of Soya and Gore-Tex the world does not need to slaughter the staggering quantity of animals it currently does for food and clothing. Statistically vegetarians live longer than carnivores so we also harm ourselves, our wallets and the environment by continuing to consume so much meat. Plus with the current obesity crisis soaring out of control across the globe there are serious reasons to drastically reduce meat consumption.

But to return to my raging emotions after the Corrida and how this distilled into the viewpoint that, for me today, makes sense of it and disabuses the often overly sentimental and indeed hypocritical stance of many in the anti-bullfighting lobby. My Damascene moment came when I realised that in terms of sheer numbers modern industrial methods of meat production dwarf all others types of animal suffering by a substantial volume, and quite possibly also in the level of cruelty inflicted.

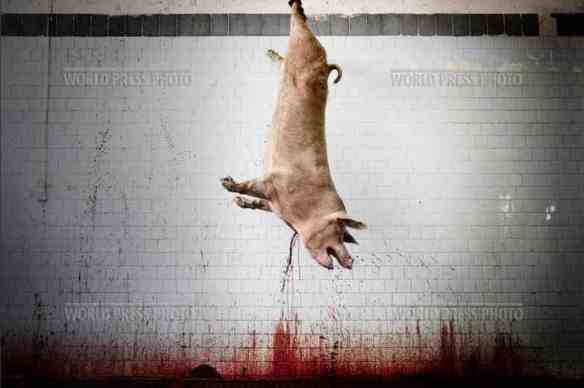

The animal kingdom has known many types of pain and misery for millions of years. However, the Agricultural Revolution created completely new kinds of suffering. That animals, wild or domesticated, have physical, emotional and social needs and are capable of feeling pain, fear and loneliness has to be taken as a given in any discussion on the ethics of killing for pleasure. Thus, a large majority of domesticated animals not only live in conditions that go against their natural requirements, but their deaths are also not quite as ‘clean’ as we like to imagine as we grill our pork chops – if we ever even trouble to give it a thought. The industrialised process runs on tight deadlines and even tighter profit margins: often the bolt guns used to kill only daze the animals who remain conscious or wake up whilst they are being ‘processed’. It is important to remember that the reason for this horror is ultimately ‘entertainment’, pure and simple, just so that we can satisfy our craving for another burger.

The ‘Toro Bravo’ by comparison leads what might be considered a privileged existence: they remain with their mother for the first year (unlike their domesticated cousins who are removed as soon as possible) and are then put out on vast tracts of prime land to graze for at least 4-years (but no more than six). In fact the ‘Dehesa’, a lightly wooded natural pastureland, covering large parts of Spain that is mostly given over to raising bulls for the arena amounts to one of the largest areas of pristine wilderness left in Europe and is a true wildlife haven. Compare this to the crates, cages and grass-free intensive feeding lots that are the industrial animals designated environments. The fighting bulls are well looked after on their way to the arena and are not crammed in lorries for hours on end: on release into the arena they will endure no more than 15-minutes before their end which is usually delivered with great skill and swiftness.

The comparison between a Corrida and industrial ‘processing’ is reasonable because the ‘Toro Bravo’ ends up in the food chain just as much as his Holstein-Friesian cousin does. The Corrida is, from this perspective, just another way we unnecessarily end the lives of cattle we have unnecessarily bred. At this moment in time I feel that the welfare of the fighting bull is superior to that of his meat-and-milk-on-legs cousins, in so far as his is the life and death that I would choose.

Enjoyed our discussions on this. Well written and great photos!

LikeLike